All the way uptown, Columbia University’s Department of Latin American and Iberian Cultures and the Hispanic Institute currently are functioning inside a beautiful, classic townhouse named the Casa Hispánica. Located on W116th st, between Broadway and Riverside Drive in the Morningside Heights area, the Casa Hispánica functions in a 14,500 square foot townhouse that was built in 1906 by the architect, Thomas Nash. There, the location is dedicated to the Hispanic Institute for Latin American & Iberian Cultures at Columbia University, where both undergraduate and graduate students are able to access a scholastic center whose aim is to provide an education and information on issues and themes pertaining to the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America. Its beginnings were in 1920, when the institute was first named, Instituto de las Españas. Since the 1920s, at the same time where “Little Spain” in Greenwich Village and Chelsea was forming as a colony, Casa Hispánica grew to be a place of interest for Spanish intellectuals abroad and in New York to congregate and showcase public conferences on Hispanic and Lusophone studies.

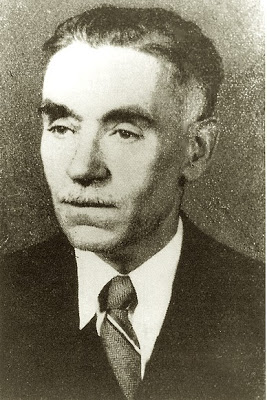

The director of the Instituto de las Españas was Federíco de Onis, a Spanish-American writer born in Salamanca, Spain who came to become a professor at Columbia University. He dedicated about 30 years to the institution in the United States, taking part in the cultivation and introduction of Hispanísmo in the country. There, he had invited important Spanish figures of the likes of Gabriel Garcia Lorca, and when the Spanish Civil War had begun, the Instituto evolved to be a hotbed of intellectual exiles in support of the Republican cause.

Individuals like Federíco de Onis pertained to a movement in the early 20th century during World War I of Spaniards arriving to the United States to take part in the surging trend of Hispanismo within the U.S. foreign language sphere. Due to ongoing conflict with Germany, the German language had lost its place as being the foreign language that was mostly promoted and taught in U.S. schools and universities, and consequently, Spanish had evolved to become a leading choice. As Professor and Historian James Fernandez notes in his essay, “Longfellow’s Law: The Place of Latin America and Spain in U.S. Hispanism”, the Spanish language had attained mass popularity in the first decades of the 20th century due to its utility and practicality. Given the possibilities of business prospects in the southern Spanish-speaking republics of Latin America, learning Spanish became to be seen as an opportunity to profit off an emerging sector. This aspect of Hispanismo contradicted with the thought of seeing the Spanish language as a gateway to learning more about the cultural, political aspects and contributions of old-world Spain and its influences in the American continent. Scholars invested in the development of Hispanismo felt this aforementioned tension between these two differing motivations for studying Spanish in the U.S.

Spaniards like Federíco de Onis felt compelled to work towards establishing Hispanic Studies in the United States as a field of academic and societal prestige rather than one of financial pragmatism, focusing more on the importance of Spain’s role in the Americas. As a philosopher from Salamanca, de Onis wrote a encompassing entries for one of the first Hispanic academic journals, Hispania, about the popular educational movement for all things Spanish and its competing factions of thought. In a letter to his Spanish colleagues on the peninsula, he made remarks about the precise moment:

“There has always been a small but select group of individuals in the United States that has made of our Spain an object of their love and devotion. The names of Washington Irving, Longfellow, Prescott, Ticknor, Lowell, and Howells come immediately to mind. When, in 1914, those great nations involved in the European war were forced to abandon their foreign trade, the United States saw, with keen instinct, the unique possibility of taking over those markets and developing in them their own commerce and export industry. It was then that a collective frenzy began to manifest itself, the ardent desire to learn Spanish. The Spanish language was the tool that would permit North Americans to understand, and carry out commerce with, Hispanic America. But to carry out commerce properly is a difficult task. Knowing the language is not enough; one must also know the nations that speak it, their tastes, their character, their traditions, their psychology, their ideals; in order to achieve this, one must know their history, their geography, their literature, their art. The Latin American nations are the offspring of Spain; one must, then, go to the source and become knowledgeable about Spain.”

Locations like the Casa Hispánica in New York became areas of academic discussion for the development of Hispanic Studies in the U.S. during the 1920s by a few dedicated Spanish scholars like Federico de Onis, and the legacy of early Hispanismo has permeated itself throughout many academic institutions through North America.

To read more information about Casa Hispánica, click here